Where Horror Gets Studied, Skewered, and Celebrated.

Newest articles and reviews

By. Professor Horror

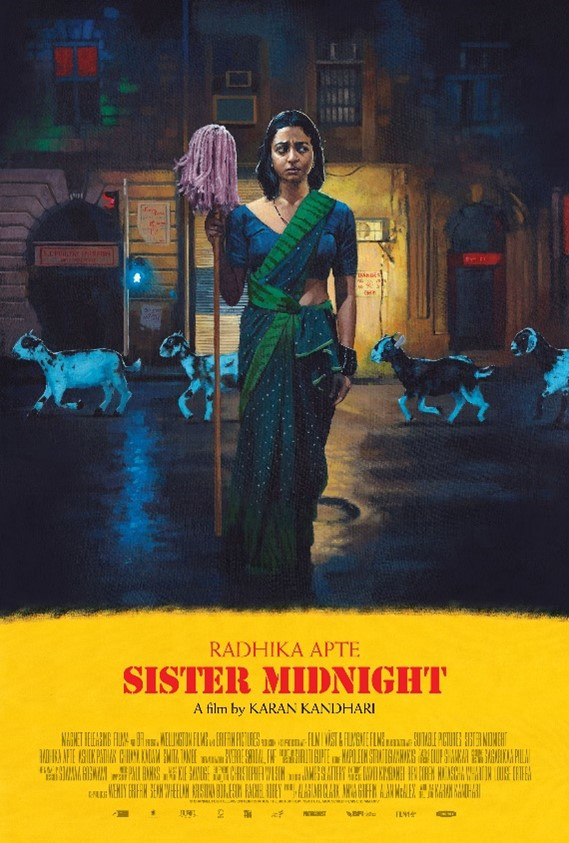

Karan Kandhari’s SISTER MIDNIGHT is a strange and striking film that quietly burrows into your eyes and mind before transforming in unexpected ways. Set in India and brimming with saturated colors, deliberate silences, and offbeat surrealism, the film uses its quiet surface to mask a much deeper unrest. With a slow burning (sometimes absurdist sensibility) Kandhari examines themes of alienation, marital confinement, and female transformation, and she does so not with the blunt force often associated with horror but through mood, imagery, and subversive humor. Shot with great attention to detail and an eye for texture, SISTER MIDNIGHT is visually rich and emotionally restrained, which lets the quiet pressure build until its protagonist begins to shatter the symbols of her confinement and carve out a path toward something stranger (and freer).

The story follows a newly married couple, Uma (Radhika Apte) and Gopal (Ashok Pathak), whose union was arranged and unromantic from the start. The film starts with their first night together as husband and wife. They undress for bed while exchanging no words (only uncomfortable stares) and the loudest sound in the room is the clattering of Uma’s green glass bangles. It’s a beautifully tense opening and captures the hollow space where intimacy should be. Uma’s bracelets rattle with every movement (filling the silence between them) and become the soundtrack of her discontent. While the opening to the film resists exposition, these bangles speak volumes.

These bracelets are not merely accessories. In some regions of Indian there is a tradition that green bangles are often worn by married women as a symbol of their new marital status. They’re gifted to the bride and expected to be worn constantly, only removed when they break naturally, a custom meant to uphold the sanctity of the marriage. For Uma, however, they are noisy shackles. Their persistent clinking becomes a kind of taunt or a constant reminder of a life she never asked for. In Kandhari’s hands, these bangles become a poetic device as they act as a symbol of Uma’s forced identity and a literal barrier to silence and peace.

As the honeymoon period ends (or arguably never begins), Uma’s new life reveals itself to be one long, tedious, and lonely stretch. Gopal, it turns out, didn’t want a partner. He wanted a quiet, obedient wife to cook, clean, and merely exist in his house. Uma, with her filthy mouth, sarcastic wit, and inability to even make rice, is not what he bargained for. But it’s this contrast that breathes life into the film. Uma is not a silent victim. Instead, she’s a firecracker wrapped in silk, and the more the world tries to confine her, the louder her resistance becomes.

The film masterfully lulls us into a false sense of mundaneness. Days pass, blending into each other with no clear sense of time. Uma has no one to talk to, and she has to beg people to speak to her. Even when she and Gopal begin to exchange words, the loudest part of the conversation remains the bangles as they clink like chains with every physical gesture. It’s a clever audio cue because while the world may not acknowledge her, Uma’s discontent cannot be ignored. Desperate for purpose, Uma takes a job, hoping that some independence might offer reprieve. But the job (like her marriage) brings more of the same: routine, drudgery, and isolation.

The mise en scène of the film reinforces this emotional detachment beautifully. Kandhari uses deep focus to constantly remind us of the bustling city outside, a city Uma is physically in but emotionally excluded from. The frames often place her alone in dark, cluttered rooms or in separate spaces from others, which visually suggests her entrapment. The longer she stays in this imposed life, the more unrecognizable she becomes. Her skin grows pale, her features sharpen, and she begins to physically transform. When she seeks medical help, doctors find nothing. No one can explain her symptoms. But the audience knows: this is not illness, it’s a metamorphosis.

The movie isn’t just about feeling stuck, it’s about becoming stuck. It’s about a woman who loses her reflection in the mirror and starts to see something else entirely. And as her world grows stranger, so too does the film’s tone. Kandhari slowly introduces moments of offbeat, even grotesque humor. There are absurd sequences that draw laughter and discomfort in equal measure, especially as Uma transitions from a bored housewife into something far more feral. Her movements become unpredictable, her reactions animalistic, and yet it’s all framed with a kind of dry, deadpan wit. We’re watching a transformation, but it’s less Cinderella and more Kafka, except here, the monster is liberation.

SISTER MIDNIGHT is a story about what happens when a woman is told to be quiet for so long, she becomes something that can only scream. Kandhari’s film is both a celebration and a lament, as she creates a slow dive into the absurdities of tradition and the desperation of silence. Marriage isn’t for everyone. And for some, it’s not even a life, it’s a sentence. SISTER MIDNIGHT doesn’t just tell that story. It rattles it, shatters it, and lets it loose into the night.

Grubby's Hole

About Professor Horror

At Professor Horror, we don't just watch horror: we live it, study it, and celebrate it. Run by writers, critics, and scholars who've made horror both a passion and a career, our mission is to explore the genre in all its bloody brillance. From big-budget slashers to underground gems, foreign nightmares to literary terrors, we dig into what makes horror tick (and why it sticks with us). We believe horror is more than just entertainment; it's a mirror, a confession, and a survival story. And we care deeply about the people who make it, love it, and keep it alive.