Where Horror Gets Studied, Skewered, and Celebrated.

Newest articles and reviews

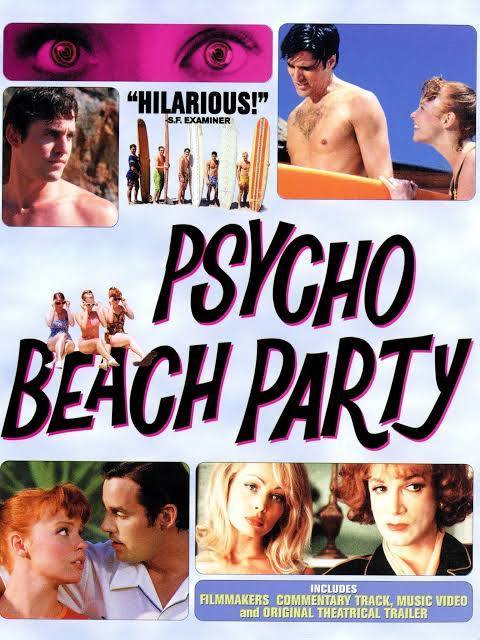

“Everything copacetic?” PSYCHO BEACH PARTY shows the Dangers of Compartmentalizing Queer Identity.”

By: Professor Horror

In an often painfully heterosexual society, anyone who deviates from the forcefully constructed binary of the dating world risks feeling excluded or even questioning their ability to be normal. PSYCHO BEACH PARTY, a campy horror-comedy written by and co-starring Charles Busch, uses the absurd framework of beach party pastiche to explore the psychological consequences of conformity (particularly for queer and gender-nonconforming individuals). Florence "Chicklet" Forrest, played by Lauren Ambrose (Yellowjackts, Six Feet Under), watches as the beachgoers around her pair off into neatly gendered couples, performing the expected rituals of heterosexual desire. But beneath the sun-soaked surfaces and carefree vibes, attraction does not always follow the rules. Some characters experience queer desire, which remains buried under layers of repression. The film uses the familiar horror trope of split personalities to illustrate the emotional turmoil and danger that can arise when one is forced to deny their identity.

As the beach party unfolds, a series of murders interrupts the fun. At first, the killings seem random, but soon it becomes clear that the victims all share one thing in common. Each of them has been labeled as "different." The killer, like society itself, polices deviation from the norm. The film implies that only by accepting themselves can the characters avoid psychological collapse and literal death. While the narrative delivers humor and over-the-top theatrics, it is grounded in a serious critique of identity repression. (It should be noted that the film contains outdated and problematic representations of mental illness and disability, which require critical viewing). However, when read through a queer lens PSYCHO BEACH PARTY becomes a surprisingly poignant coming-of-age horror film. It blends the aesthetic of 1960s surf movies with the violence and morality tales of 1980s slasher films. The result is a film that feels absurd, playful, and emotionally honest. In fact, the strange premise and extreme camp might make viewers feel as if John Waters moved from Baltimore to Malibu.

The film begins with a bizarre cold opening in which a James Dean-style rebel falls for a mysterious woman in a diner. When he tries to approach her, he discovers that she has three heads, which quickly turns his affection to disgust. This surreal moment turns out to be a movie within the movie, playing at a drive-in. The real narrative takes place in the parked cars around the screen. As we shift from this film-within-a-film into the main story, the visuals change from black and white to vibrant color. This transition is not just a technical flourish but a symbolic one. It mimics the shift in The Wizard of Oz and acts as a quiet nod to queer identity, invoking the phrase "friend of Dorothy" as a coded way of identifying LGBTQ individuals. More importantly, the odd opening scene introduces key themes of self-concealment and performance. The woman with three heads becomes a metaphor for people forced to wear multiple faces, one for every social expectation. Moerver, this scene sets up the psychological concept of compartmentalization, the belief that a person can separate their desires from their public identity without facing consequences.

This idea runs throughout the film. Chicklet is styled after the Gidget archetype, the wholesome teen girl from 1960s beach films, but she refuses to conform to gendered expectations. She does not want to admire the surfers from the sidelines. Instead, she wants to become one. Chicklet idolizes the carefree, rebellious surfer lifestyle and attempts to claim it for herself. But when her interests and appearance fail to gain her acceptance, she disappears, and another persona takes her place. Anne Bowman (also played by Ambrose) is bold, sexually assertive, and unashamed. While Chicklet tries to form a heterosexual relationship with the hunky Starcat (Nicholas Brendon), her internal conflict mirrors that of many queer individuals who feel forced to perform straightness. Chicklet’s compartmentalization reflects the lived experience of many LGBTQ people who separate public and private selves in order to survive. Anne Bowman represents the repressed desire Chicklet cannot express, and Bowman’s appearances grow more frequent and violent. The more Chicklet suppresses her true self, the more destructive her alter ego becomes.

As Chicklet experiences blackouts and psychological distress, she begins to fear that she may be responsible for the murders. Her fear becomes a metaphor for what can happen when people are denied space to express their full identities. Suppressing queerness, denying desire, and performing a false self can result in serious emotional and psychological harm. The film turns this internal crisis into a literal horror story, with a body count to match. Through this lens, PSYCHO BEACH PARTY suggests that the danger is not in being queer, but in pretending not to be.

Although Chicklet’s journey appears to lean toward heterosexual romance, the rest of the film offers a broader, more inclusive vision of queerness. Two members of the surfer gang, Provoloney (Andrew Levitas) and Yo-Yo (Nick Cornish), engage in frequent shirtless wrestling sessions that initially read as performative masculinity. Over time, however, these physical encounters evolve into romantic intimacy, culminating in the two men openly dating. Their storyline challenges stereotypes of male friendship and allows space for affection between men to be seen as valid and real. Meanwhile, Chicklet’s best friend Berdine (Danni Wheeler) clearly harbors romantic feelings toward her, adding another layer to the film’s queer dynamics. Berdine’s quiet longing and loyal presence reflect the struggles many queer individuals face when their feelings are not reciprocated or acknowledged. The subplot further reinforces the emotional stakes of living inauthentically.

Detective Monica Stark (played by Charles Busch in drag) investigates the murders and eventually uncovers the killer’s motive. This revelation is not subtle, but it is powerfully effective. It frames the film’s central theme: nonconformity is dangerous not because it is deviant, but because society refuses to allow it to exist peacefully. The solution, then, is not to hide but to embrace difference. The beach party guests must abandon their performances and claim the parts of themselves they were once afraid to show.

For LGBTQ youth, the process of identity development can involve risk, fear, and emotional turmoil. In many cases, young people attempt to retain elements of heterosexual identity even as they begin to acknowledge their queerness. This transitional stage can lead to internalized shame and confusion. The film dramatizes this experience and portrays the costs of remaining closeted. In PYSCHO BEACH PARTY, the threat of death ultimately outweighs the fear of social rejection, which prompts characters to choose authenticity. While this resolution feels hopeful, it also shows the bleak reality that for many queer individuals, the cost of hiding is not just emotional…it can be fatal.

Despite its campy tone and comedic flair, PSYCHO BEACH PARTY offers a smart, subversive take on the relationship between identity, repression, and danger. It is a horror film that understands the real monsters are the systems that force people to deny who they are. Beneath the slapstick and sunburns is a sincere message: pretending to be someone you are not may help you fit in, but it will never help you live fully. And in the end, survival( emotional, psychological, and literal) depends on letting your true self be seen.

Grubby's Hole

About Professor Horror

At Professor Horror, we don't just watch horror: we live it, study it, and celebrate it. Run by writers, critics, and scholars who've made horror both a passion and a career, our mission is to explore the genre in all its bloody brillance. From big-budget slashers to underground gems, foreign nightmares to literary terrors, we dig into what makes horror tick (and why it sticks with us). We believe horror is more than just entertainment; it's a mirror, a confession, and a survival story. And we care deeply about the people who make it, love it, and keep it alive.