Where Horror Gets Studied, Skewered, and Celebrated.

Newest articles and reviews

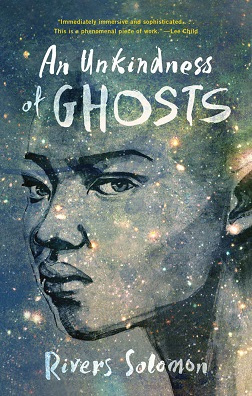

An UNKINDNESS OF GHOSTS shows why the World is the Real Monster

By. Professor Horror

Life aboard the HSS Matilda is structured to break bodies...and then blame them for failing.Rivers Solomon’s AN UNKINDNESS OF GHOSTS is an important work of speculative fiction that places disability at the center of its world-building rather than treating it as metaphor, symbol, or narrative obstacle. Set aboard the HSS Matilda, a generation ship traveling through deep space, the novel imagines a rigid social order modeled explicitly on the antebellum American South. The ship is divided into decks that determine race, class, labor, education, and access to medical care, producing a closed system in which hierarchy is naturalized and suffering is routine. This hierarchy reproduces the racial logic of slavery, with Black and brown bodies concentrated in the lowest decks and subjected to the greatest deprivation. Hunger, injury, and untreated illness are not exceptions aboard the Matilda; they are the cost of keeping the ship orderly. At the center of this world is Aster Grey, a young, neurodivergent healer living in the ship’s lowest decks, where survival is precarious and authority is enforced through punishment rather than protection. From the outset, Solomon establishes disability not as a marginal theme but as a fundamental condition of life aboard the Matilda. Bodies are shaped by deprivation, trauma, and neglect, therefore impairment emerges not as individual failure but as a predictable outcome of environmental design.

Early in the novel, Solomon offers a scene that decisively reframes how disability will function throughout the story. A young child faces the possibility of amputation, yet the fear expressed is not of disability itself, but of the pain the procedure will cause. The child does not imagine life as unlivable after the loss of a limb, but instead they fear suffering without relief or care. This moment quietly establishes the novel’s central argument: disability is not the horror. The true horror lies in an environment that allows pain to persist, withholds adequate resources, and treats bodily harm as acceptable collateral damage. Solomon deliberately redirects the reader away from familiar narratives of disability as tragedy or loss and toward the systems that make injury catastrophic. From this point forward, disability is framed as a lived reality shaped by context rather than an intrinsic condition to be feared.

Aster’s role as an unofficial healer further grounds this critique. Barred from formal medical education because of her deck status, she obsessively studies anatomy, illness, and treatment through stolen books, observation, and experimentation. Her neurodivergence (marked by intense focus, difficulty navigating social norms, and emotional guardedness) is neither romanticized nor pathologized. Instead, it becomes essential to her ability to survive and care for others in a world that refuses to recognize her competence. Aster’s relationships are complicated and often painful, particularly her unstable bond with the Surgeon, which offers moments of intimacy alongside betrayal and risk. The absence of Aster’s mother, who was institutionalized by ship authorities, haunts her understanding of medicine and power, reinforcing how medical systems function as tools of control.

These relationships reveal how deeply the ship’s hierarchy penetrates family, memory, and identity. Solomon’s world-building is meticulous and unsettling precisely because it feels mundane. The Matilda is not a sleek, wondrous vessel but a decaying structure sustained through routine violence and bureaucratic order. Officers enforce discipline through humiliation, punishment, and surveillance, cloaking cruelty in the language of necessity and tradition. Medical spaces are sites of monitoring as much as care, where diagnoses can justify confinement rather than healing. Food scarcity is normalized, labor assignments routinely produce injury, and constant observation fractures trust between inhabitants. So when Aster uncovers the truth behind her mother’s institutionalization and the ship’s governing logic, her efforts to heal others become inseparable from confronting the system that depends on their suffering. The tension of the novel lies not in whether the system is cruel (it already is) but in how long anyone can survive inside it without becoming complicit.

Although often categorized as science fiction, UNKINDNESS OF GHOSTS is, at its core, a work of institutional horror. Its most frightening scenes unfold not in moments of chaos, but in bureaucratic calm…in orders followed, rules enforced, and procedures carried out without empathy. Authority figures rarely need to be overtly monstrous because their power is already legitimized by policy and tradition. Solomon understands that horror emerges most forcefully when violence is framed as reasonable, inevitable, or corrective. In this sense, the novel feels less speculative than disturbingly familiar, echoing real histories of medical abuse, racialized confinement, and structural neglect. The ship’s horrors are effective precisely because they resemble systems readers already know. As the narrative develops, Solomon gradually reveals that the ship’s hierarchy is not accidental or merely inherited, but deliberately designed and maintained. Secrets surrounding the Matilda’s governance and purpose recontextualize earlier moments of suffering, emphasizing structure over individual cruelty. Yet the novel resists the fantasy that revelation alone can undo harm. Knowledge does not erase trauma, restore bodies, or repair relationships damaged by years of neglect. Instead, Solomon focuses on quieter forms of endurance: shared knowledge, mutual care, and refusal to internalize narratives that frame suffering as deserved. Resistance here is fragile, costly, and deeply constrained, shaped by the same environment it challenges.

Crucially, AN UNKINDNESS OF GHOSTS rejects cure as a narrative endpoint. Disability is not something that must be eliminated in order for justice to be imaginable. What disabled characters need are resources: consistent food, safety, autonomy, and access to care without punishment or surveillance. Survival depends not on normalization, but on interdependence and ethical refusal. Solomon’s disability politics insist that the problem is not broken bodies, but systems that demand those bodies endure harm in order to function. By refusing the promise of restoration, the novel exposes how deeply invested oppressive systems are in maintaining suffering. AN UNKINDNESS OF GHOSTS will resonate strongly with readers interested in speculative fiction that interrogates power rather than escaping it. Fans of Octavia Butler, N.K. Jemisin, and Samuel R. Delany will recognize Solomon’s commitment to world-building as social critique. Readers drawn to horror rooted in institutions (medical, carceral, colonial) rather than monsters will find the novel profoundly unsettling. It is also essential reading for those interested in disability studies, Afrofuturism, and narratives that challenge the assumption that bodily difference is inherently tragic. Solomon does not offer comfort, catharsis, or easy moral clarity. Instead, they offer something far more unsettling: a world that feels horrifying precisely because it asks how much suffering we are willing to call normal.

About Professor Horror

At Professor Horror, we don't just watch horror: we live it, study it, and celebrate it. Run by writers, critics, and scholars who've made horror both a passion and a career, our mission is to explore the genre in all its bloody brillance. From big-budget slashers to underground gems, foreign nightmares to literary terrors, we dig into what makes horror tick (and why it sticks with us). We believe horror is more than just entertainment; it's a mirror, a confession, and a survival story. And we care deeply about the people who make it, love it, and keep it alive.